The Public Option: How Smart Tariff Subsidies Can Boost Minigrids and Solve Africa’s Rural Energy Access Dilemma

When it comes to operating private minigrids, the overarching expectation is that such projects need to be commercial in order to attract the long-term private infrastructure capital they need to grow. However, many African governments are unwilling to allow cost-reflective pricing regimes, which is a critical piece in the bankability puzzle. While government actions to control prices are often well-intentioned and aimed at consumer protection, the often-unmentioned yet salient requirement is that private minigrids’ prices (i.e.: tariffs) should be close to – and in some cases almost at parity with – the tariffs charged by national utilities. However, most of these utilities are insolvent, and they provide poor service. Moreover, a typical public utility enjoys significant direct and indirect subsidies, either through funding allocations for capital and operational costs from the public fiscal budget and/or from international donor contributions, or via cross-subsidization between their urban and rural customers.

There is also considerable debate about whether minigrids or utilities are better positioned to reach rural customers in Africa. But this debate almost entirely ignores the question of whether utilities have the operational viability to extend their grids, given their massive insolvency and systemic poor service. Minigrids are better positioned to optimize their service quality and value proposition for the end user. Yet the expectation that minigrids should offer cost parity with utilities forces private minigrid developers to grapple with a difficult balancing act in their desire to achieve social outcomes while also realizing commercial returns. This makes rural electrification challenging, to say the least.

A LESSON FROM EUROPE

A few decades ago, the developed world faced a similar dilemma in their own energy sectors. But their challenge was somewhat different, in the sense that the concern at the time was how best to lower the power generation costs for renewable energy projects. This challenge led to the birth of feed-in tariffs.

In the 1970s and 1980s, feed-in tariffs (FITs) emerged as part of some countries’ efforts to diversify their energy mix and encourage new players to invest in the grid network. FITs were essentially sale agreements between power generating companies and grid utilities/distributors, in which the tariff (i.e.: the amount the grid network paid to these companies for the electricity they fed into the grid) was set by the government. The government priced these feed-in tariffs at a rate that guaranteed renewable electricity generators a set price for their power, giving them the confidence to invest in providing energy to the grid network.

The first FIT was launched in 1978 under the U.S. Public Utilities Regulatory Policies Act, but the approach gained particular traction in Europe in the subsequent years. Germany’s first national-level FIT came into force in 1991, and was based on a percentage of the residential retail price of electricity. Later, the U.K. and Spain would implement FIT policies to support their own clean energy sectors. The main objective was to de-risk eligible renewable energy projects by giving them guaranteed contract conditions and standardized pricing for their energy, allowing them to attract more private investment and to gradually establish themselves as viable alternatives to traditional energy providers.

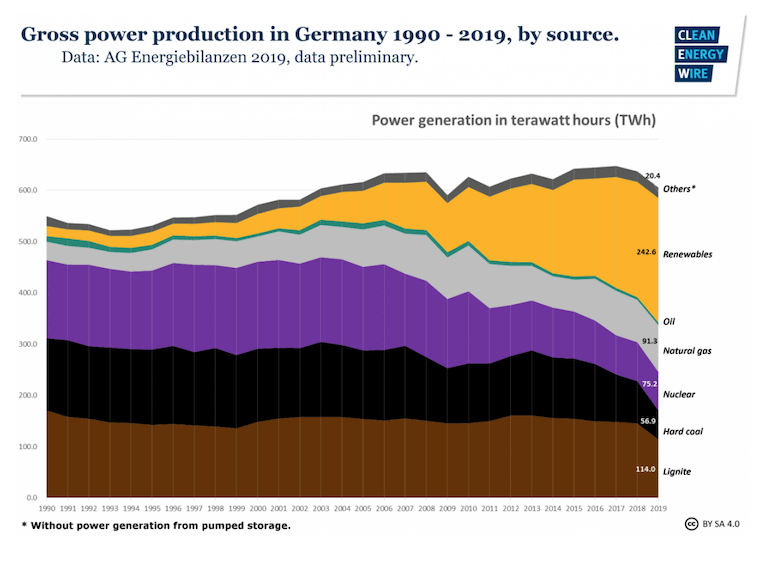

These policies had their intended results, leading to increased long-term clean energy investments, transparency and clarity that effectively lowered risks and enhanced the bankability of renewable energy projects. FIT policies ushered in a new wave of innovation that altered Europe’s energy mix and created the beginnings of a pathway to sustainability. The time series graph below shows how FIT policies increased the deployment of renewables in Germany.

Source: Clean Energy Wire

THE IMPLICATIONS FOR RURAL AFRICA

From the FIT programs across Europe, we learn that government action to support renewable energy can lead to significant cost reduction and scale if well-implemented. Indeed, the Africa Minigrid Developers Association (AMDA)’s Benchmarking Africa’s Minigrid study showed that public funding works. Time-bound and smartly designed tariff subsidies, through which the government would pay a portion of the cost of each kilowatt hour of energy customers purchase from minigrids, would allow customers to pay a lower amount than they would in a purely commercial situation. This can help to bridge the affordability gap, as renewable energy developers work on demand growth in order to enhance their bankability and expand into rural areas.

Evidence from the CrossBoundary Innovation Lab illustrates the positive impact of lower energy prices on consumption and electricity demand. CrossBoundary provided some minigrid developers in Tanzania with a subsidy that allowed them to lower their prices by 50-75% for some rural consumers, while still recovering their costs. The results showed that this reduced pricing increased energy consumption. For instance, the study discovered that customers increased their consumption by 1.5-3x from baseline levels after two years, following the introduction of the subsidy. Moreover, the consumers with the lowest energy consumption increased their consumption by 5x, which shows that their low electricity use was caused by budget factors, not a lack of demand. What this means is that using subsidies to lower pricing will actually support increased energy consumption and move companies closer to commercial viability faster than higher pricing. Moreover, these subsidies have a greater impact on lower-income customers, a contrast to other subsidy programs in the electricity sector whose structuring is regressive in their distribution, thus unintentionally favoring the non-poor over the poor.

CONCLUSION

It is easy to see how subsidy-adjusted pricing could play a part in a country’s low-cost electrification efforts. Governments could easily use the capital expenditure savings they realize from leveraging private sector minigrids (rather than extending the public utility grid) to provide subsidies that reduce consumer pricing for minigrid electricity for a limited period of time. Alternatively, the funding for minigrid subsidies could be sourced by reallocating a country’s committed fossil fuel subsidies into programs that support renewable energy. This would act as a key driver in moving a country towards a green future. The subsidized portion of the price of minigrid electricity could then be stepped down over time, in response to evidence of increased consumption due to new income-generating activities or assets among customers, such as mills, welding, irrigation, cold storage, etc. As their customers’ income grows, so would the minigrid companies themselves. Though the cumulative subsidy would initially be higher as new minigrids are built, over time the subsidy spending per site would decline, as older minigrid sites start realizing higher energy consumption levels as they move toward a targeted peak level.

Such a structure would incentivize the minigrid developer to concentrate on demand growth innovation, like financing customers’ purchase of appliances and other assets that consume a higher electricity load. Meanwhile, the public utility could focus on strengthening the existing grid infrastructure, thus deploying taxpayer capital more efficiently. The time-bound nature of this sort of government subsidy fund would make it more appealing to a potential donor who may be apprehensive about being locked into a perpetual subsidy with no exit or end in sight, similar to the current donor support provided to traditional utilities.

The World Bank estimates that minigrids can provide electricity for up to 500 million people by 2030. Further, the bank projects that the cost of minigrid electricity per kilowatt hour will decrease by two thirds in the same period. While these goals are quite achievable, they can only be realized at the intersection of effective public policy, scale and innovation. A smartly designed tariff subsidy program to reduce the cost of minigrid power for the unelectrified is the critical missing piece in these efforts.

Daniel Kitwa is an Energy Access Finance Advisor at the Africa Minigrid Developers Association (AMDA).

Visit source: https://nextbillion.net/tariff-subsidies-minigrids-africa-rural-energy-access